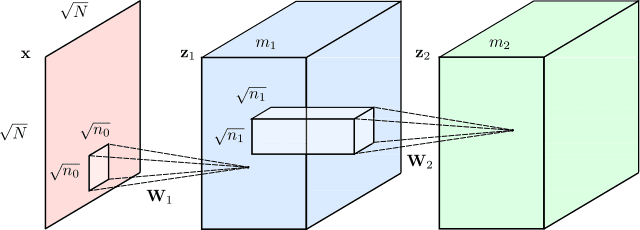

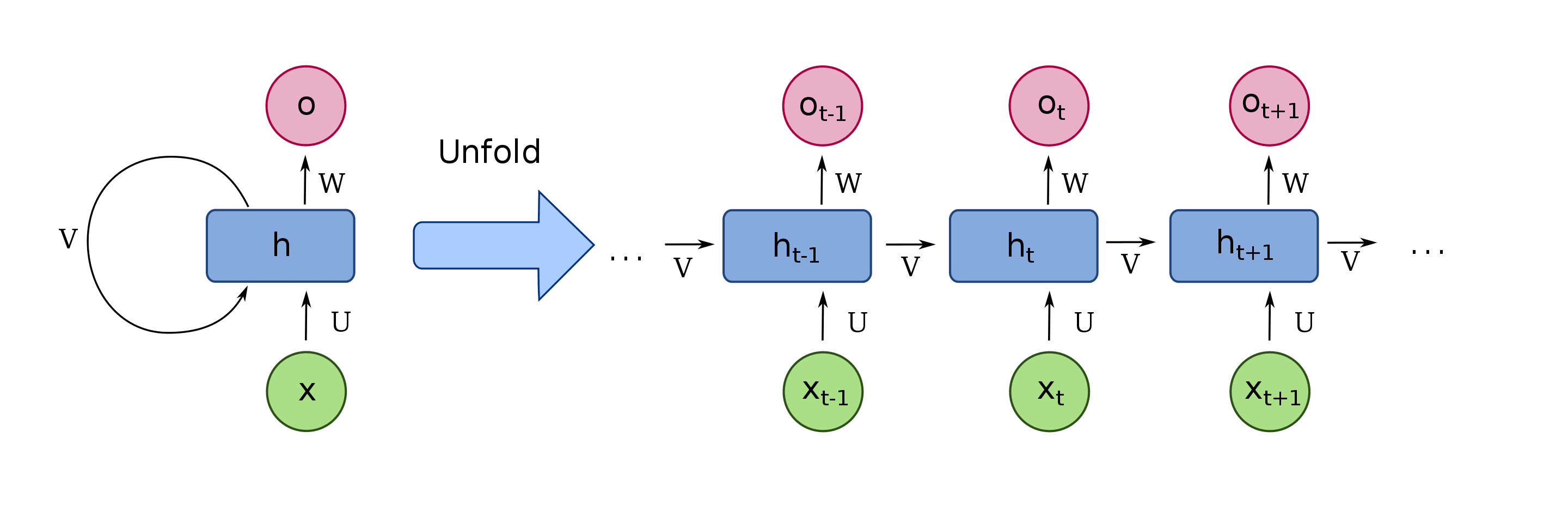

If you want to stay hip in machine learning and especially NLP, you have to know at least a bit about Transformers. So in this post, we’ll talk about what they are, how they work, and why they’ve been so impactful. A Transformer is a type of neural network architecture. To recap, neural nets are a very effective type of model for analyzing complex data types like images, videos, audio, and text. But there are different types of neural networks optimized for different types of data. For example, for analyzing images, we’ll typically use convolutional neural networks or “CNNs.” Vaguely, they mimic the way the human brain processes visual information. And since around 2012, we’ve been quite successful at solving vision problems with CNNs, like identifying objects in photos, recognizing faces, and reading handwritten digits. But for a long time, nothing comparably good existed for language tasks (translation, text summarization, text generation, named entity recognition, etc). That was unfortunate, because language is the main way we humans communicate. Before Transformers were introduced in 2017, the way we used deep learning to understand text was with a type of model called a Recurrent Neural Network or RNN that looked something like this: Let’s say you wanted to translate a sentence from English to French. An RNN would take as input an English sentence, process the words one at a time, and then, sequentially, spit out their French counterparts. The key word here is “sequential.” In language, the order of words matters and you can’t just shuffle them around. The sentence: “Jane went looking for trouble.” means something very different from the sentence: “Trouble went looking for Jane” So any model that’s going to understand language must capture word order, and recurrent neural networks did this by processing one word at a time, in a sequence. But RNNs had issues. First, they struggled to handle large sequences of text, like long paragraphs or essays. By the time got to the end of a paragraph, they’d forget what happened at the beginning. An RNN-based translation model, for example, might have trouble remembering the gender of the subject of a long paragraph. Worse, RNNs were hard to train. They were notoriously susceptible to what’s called the vanishing/exploding gradient problem (sometimes you simply had to restart training and cross your fingers). Even more problematic, because they processed words sequentially, RNNs were hard to parallelize. This meant you couldn’t just speed up training by throwing more GPUs at the them, which meant, in turn, you couldn’t train them on all that much data.

Enter Transformers

This is where Transformers changed everything. They were developed in 2017 by researchers at Google and the University of Toronto, initially designed to do translation. But unlike recurrent neural networks, Transformers could be very efficiently parallelized. And that meant, with the right hardware, you could train some really big models. How big? Bigly big. GPT-3, the especially impressive text-generation model that writes almost as well as a human was trained on some 45 TB of text data, including almost all of the public web. So if you remember anything about Transformers, let it be this: combine a model that scales well with a huge dataset and the results will likely blow you away.

How do Transformers work?

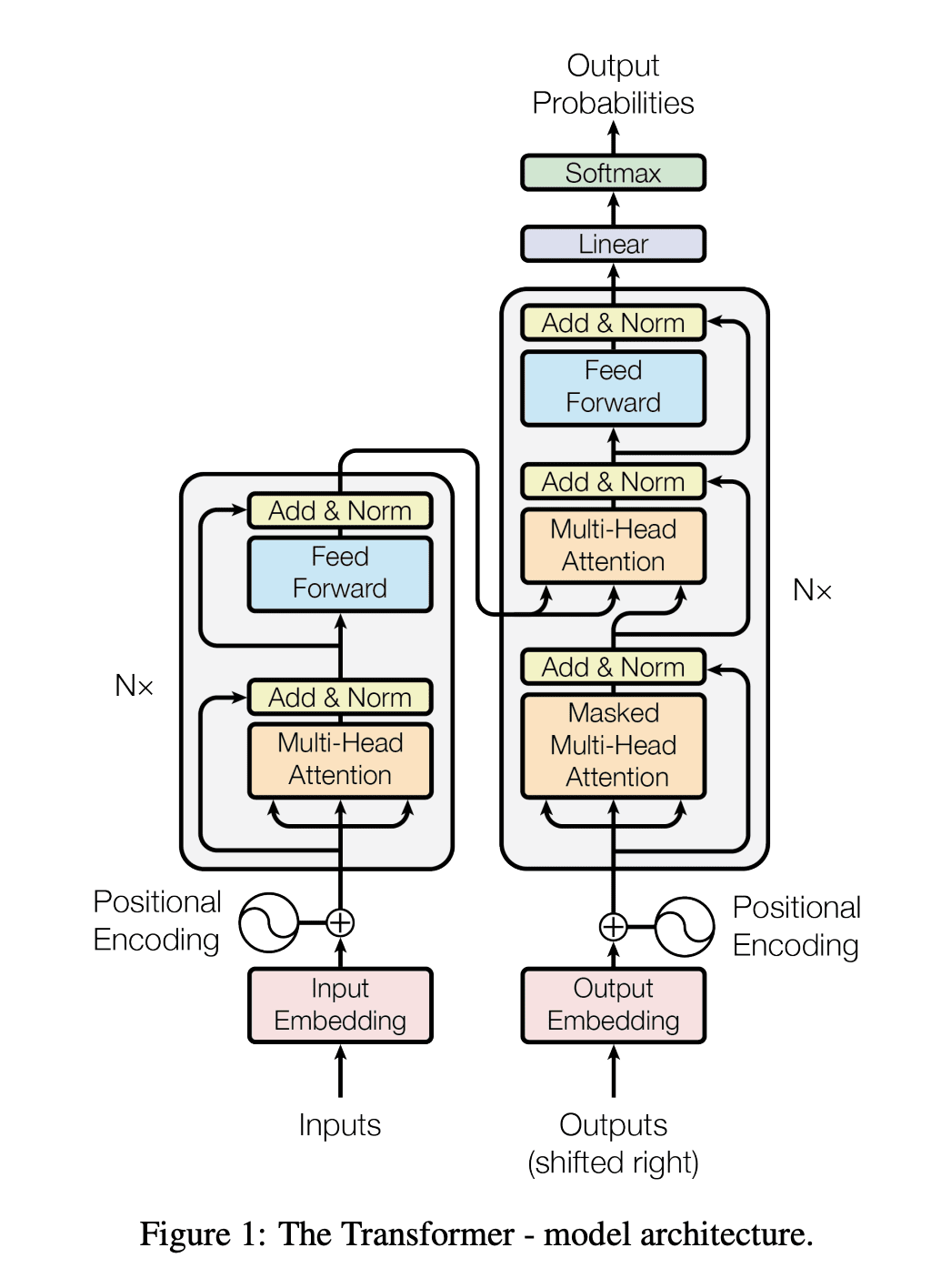

While the diagram from the original paper is a little scary, the innovation behind Transformers boils down to three main concepts:

Positional Encodings

Let’s start with the first one, positional encodings. Let’s say we’re trying to translate text from English to French. Remember that RNNs, the old way of doing translation, understood word order by processing words sequentially. But this is also what made them hard to parallelize. Transformers get around this barrier via an innovational called positional encodings. The idea is to take all of the words in your input sequence–an English sentence, in this case–and append each word with a number it’s order. So, you feed your network a sequence like: [(“Dale”, 1), (“says”, 2), (“hello”, 3), (“world”, 4)] Conceptually, you can think of this as moving the burden of understanding word order from the structure of the neural network to the data itself. At first, before the Transformer has been trained on any data, it doesn’t know how to interpret these positional encodings. But as the model sees more and more examples of sentences and their encodings, it learns how to use them effectively. I’ve done a bit of over-simplification here–the original authors used sine functions to come up with positional encodings, not the simple integers 1, 2, 3, 4–but the point is the same. Store word order as data, not structure, and your neural network becomes easier to train.

Attention

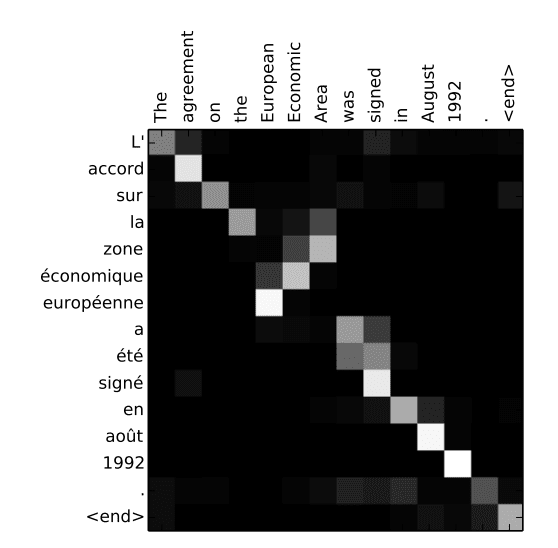

THE NEXT IMPORTANT PART OF TRANSFORMERS IS CALLED ATTENTION. Got that? Attention is a neural network structure that you’ll hear about all over the place in machine learning these days. In fact, the title of the 2017 paper that introduced Transformers wasn’t called, We Present You the Transformer. Instead it was called Attention is All You Need. Attention was introduced in the context of translation two years earlier, in 2015. To understand it, take this example sentence from the original paper: The agreement on the European Economic Area was signed in August 1992. Now imagine trying to translate that sentence into its French equivalent: L’accord sur la zone économique européenne a été signé en août 1992. One bad way to try to translate that sentence would be to go through each word in the English sentence and try to spit out its French equivalent, one word at a time. That wouldn’t work well for several reasons, but for one, some words in the French translation are flipped: it’s “European Economic Area” in English, but “la zone économique européenne” in French. Also, French is a language with gendered words. The adjectives “économique” and “européenne” must be in feminine form to match the feminine object “la zone.” Attention is a mechanism that allows a text model to “look at” every single word in the original sentence when making a decision about how to translate words in the output sentence. Here’s a nice visualization from that original attention paper: It’s a sort of heat map that shows where the model is “attending” when it outputs each word in the French sentence. As you might expect, when the model outputs the word “européenne,” it’s attending heavily to both the input words “European” and “Economic.” And how does the model know which words it should be “attending” to at each time step? It’s something that’s learned from training data. By seeing thousands of examples of French and English sentences, the model learns what types of words are interdependent. It learns how to respect gender, plurality, and other rules of grammar. The attention mechanism has been an extremely useful tool for natural language processing since its discovery in 2015, but in its original form, it was used alongside recurrent neural networks. So, the innovation of the 2017 Transformers paper was, in part, to ditch RNNs entirely. That’s why the 2017 paper was called “Attention is all you need.”

Self-Attention

The last (and maybe most impactful) piece of the Transformer is a twist on attention called “self-attention.” The type of “vanilla” attention we just talked about helped align words across English and French sentences, which is important for translation. But what if you’re not trying to translate words but instead build a model that understands underlying meaning and patterns in language–a type of model that could be used to do any number of language tasks? In general, what makes neural networks powerful and exciting and cool is that they often automatically build up meaningful internal representations of the data they’re trained on. When you inspect the layers of a vision neural network, for example, you’ll find sets of neurons that “recognize” edges, shapes, and even high-level structures like eyes and mouths. A model trained on text data might automatically learn parts of speech, rules of grammar, and whether words are synonymous. The better the internal representation of language a neural network learns, the better it will be at any language task. And it turns out that attention can be a very effective way of doing just this, if it’s turned on the input text itself. For example, take these two sentence: “Server, can I have the check?” “Looks like I just crashed the server.” The word server here means two very different things, which we humans can easily disambiguate by looking at surrounding words. Self-attention allows a neural network to understand a word in the context of the words around it. So when a model processes the word “server” in the first sentence, it might be “attending” to the word “check,” which helps disambiguate a human server from a metal one. In the second sentence, the model might attend to the word “crashed” to determine this “server” refers to a machine. Self-attention help neural networks disambiguate words, do part-of-speech tagging, entity resolution, learn semantic roles and a lot more. So, here we are.: Transformers, explained at 10,000 feet, boil down to: If you want a deeper technical explanation, I’d highly recommend checking out Jay Alammar’s blog post The Illustrated Transformer.

What Can Transformers Do?

One of the most popular Transformer-based models is called BERT, short for “Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers.” It was introduced by researchers at Google around the time I joined the company, in 2018, and soon made its way into almost every NLP project–including Google Search. BERT refers not just a model architecture but to a trained model itself, which you can download and use for free here. It was trained by Google researchers on a massive text corpus and has become something of a general-purpose pocket knife for NLP. It can be extended solve a bunch of different tasks, like: – text summarization – question answering – classification – named entity resolution – text similarity – offensive message/profanity detection – understanding user queries – a whole lot more BERT proved that you could build very good language models trained on unlabeled data, like text scraped from Wikipedia and Reddit, and that these large “base” models could then be adapted with domain-specific data to lots of different use cases. More recently, the model GPT-3, created by OpenAI, has been blowing people’s minds with its ability to generate realistic text. Meena, introduced by Google Research last year, is a Transformer-based chatbot (akhem, “conversational agent”) that can have compelling conversations about almost any topic (this author once spent twenty minutes arguing with Meena about what it means to be human). Transformers have also been making waves outside of NLP, by composing music, generating images from text descriptions, and predicting protein structure.

How can I use Transformers?

Now that you’re sold on the power of Transformers, you might want to know how you can start using them in your own app. No problemo. You can download common Transformer-based models like BERT from TensorFlow Hub. For a code tutorial, check out this one I wrote on building apps powered by semantic language. But if you want to be really trendy and you write Python, I’d highly recommend the popular “Transformers” library maintained by the company HuggingFace. The platform allow you to train and use most of today’s popular NLP models, like BERT, Roberta, T5, GPT-2, in a very developer-friendly way.